The “Patient Ferment” of Early Christianity

After Constantine’s conversion in 312 CE, the growth of the church is easy to explain, but not before (Kreider, 2016, p. 9). Up to that decisive point, Christian writings focused on church order with the theme of evangelism practically nonexistent (p. 10). Leadership structure was elaborated but didn’t include apostles or evangelists, and worship services were not used to attract new adherents (p. 10-11). Kreider refers to the mysterious, decentralized, uncoordinated spread of Christianity during that time as “patient ferment” (p. 12). Cyprian, Justin, Origen, and Tertulian emphasized the effectiveness of Christian witness as depending on their lifestyle, how their patience intrigues and attracts people to faith (p. 14-29).

The growth of Christianity was more accelerated, whose characteristic patience became degraded (p. 245, 251). Constantine “Christianized” the law, but without abandoning his “unreformed habitus” (p. 263.1-2). Ge governed according to the traditional Roman approach, favoring the church and suppressing dissidents (p. 267, 269). Constantine offered Christians control over missions endeavors (p. 274), power of state for conversion (p. 275) and suppression of dissidence (276). And the emperor was in a hurry to implement these changes to Christian practice (277).

By the 4th century, “the papacy and the imperial court seemed wobbly” and Augustine (354-430) felt “out of control” (p. 281). Augustine failed to see the corrective in the Christian habitus of patience to Roman habitus of impatience (p. 290), Augustine shifted focus in his teaching emphasizing the inward Christian life rather than on praxis (p. 290). In the 5th century Augustine’s increased anxiety leads him to shift hears encouraging political powers to use “top-down methods for Christian ends” (p. 295).

Rewiring the Convert’s “Habitus”

While after Constantine’s conversion Christianity offered social benefits, before this catechesis and worship were the two means Christian communities sought to rewire convert’s habitus (p. 41). This term refers to the deeper motivator linked to socioeconomic and psychological realities coined by Pierre Bourdieu, “corporeal knowledge” we carry in our bodies (39.2).

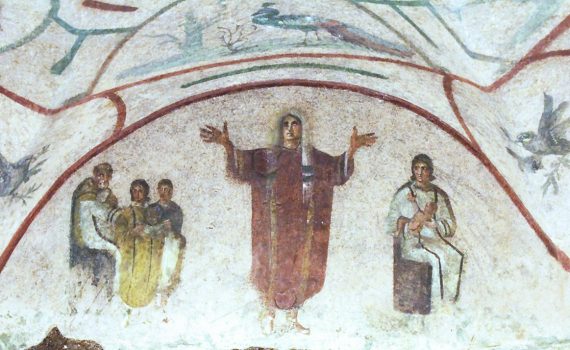

The heroic witness of Christian victims of persecution before the reign of Constantine demonstrate that they had allegiances that didn’t fit the Roman structure (p. 45). The Christians were of different social classes (p. 46). They could not control their surrounding circumstances but “they could be themselves” (p. 47). Christians used public persecution as an opportunity to witness to crowds regarding impending judgement (p. 48). Thus, such heroic Christian habitus was transmitted through role models who embodied the message (p. 50). Habitus was transmitted in the repetition of powerful phrases for context of suffering (p. 50), and the kinesthetic effects of worship (p. 51).

In the Roman world during the emergence of Christianity, private associations provided adherents with face-to-face relationships and sense of participation and responsibility (p. 52). These associations “sustained the life of local people” and “formed their habitus” (p. 56). Christianity offered an alternative association which offered some preferable conditions (p. 56). Contribution was voluntary and members saw themselves as a family which transcended gender and class boundaries (p. 59). However, Christian associations were secretive, leading to rumors of “cannibalism and sexual license” (p. 58).

The growth of Christianity before Constantine happened despite a lack of planning and control (p. 74). They believed God’s sovereignty was involved, and thus didn’t seek to discern and record strategic insights. Christians prioritized developing Christian habitus over evangelism, and believed the main agents of change were marginal members of society – the humble and anonymous (p. 74). Even during this period, however, increased numbers led to a degradation of habitus which precipitated more vigorous preaching and catechization (p. 125). Evangelization shifted in some contexts from the witness of the community to that of individual piety of monks (p. 126). Inflated communities led to a greater presence of lukewarm members (p. 135), and full meals were replaced by symbolic liturgies (p. 136).

Is Christian Habitus Attractive Today?

In my context of secular, nominally Roman Catholic Latin Europe – Portugal, Spain, and Italy – a focus on Christian practice versus doctrine has been an emphasis for some time now. The Catholic Church has taken strides to emphasize involvement in social justice and assistance of the poor. I have been impressed by the number of social projects that are present in the dioceses in the Lisbon metro area.

At the same time, my informal inquiries inform me that the number of young Portuguese Catholics doing formal catechism is low. Much more popular are small group models like Alpha Course which has been used to introduce many nominal churchgoers to a deeper understanding of the faith.

The pre-Constantine Christian emphasis on the habitus of the humble and anonymous as the primary evangelistic strategy can be restored as part of Catholic tradition. Within the Catholic Church the hierarchy’s influence is powerful and evident. But in the wider secular society, the witness of servant-hearted Christians who seek the common good is a welcome change. The predominant caricature of the church is an institution only concerned with defending the leverage of its doctrinal positions on issues such as abortion, same-sex marriage, and Christian religious supremacy.

References

Kreider, Alan. (2016). The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire. Baker Academic.